February 14, 1945 - CHEMNITZ

From the Operations Record Book:

22 aircraft and crews were briefed, and successfully took off at approximately 20.00 hrs to attack CHEMNITZ the Bradford of Germany with important rail junctions through which reinforcements from the west, country and southern Germany would have to pass on their way to the Eastern Front. The weather was good over England but deteriorated on approaching the target which was found covered with 10/10th cloud with tops up to 18,000 ft. Markers could not be seen and crews were instructed to bomb on Navigational aids. The consensus of opinion seemed to be that the attack was rather scattered. An aircraft that had bombed however went below cloud and reported that the southern part of the town was burning but the northern part was untouched. Flak was slight and there were no searchlights. Photographs reveal nothing. All aircraft returned safely to base after their nine hours trip.

---

---

LIVE OPERATION: CHEMNITZ

CREW:

• F/O Robert Douglas Harris (Pilot) RCAF• SGT Kenneth John Boucher Smith (Flight Engineer) RAF

• F/SGT David Johnston Yemen (Navigator) RCAF

• F/O Gordon James Nicol (Air Bomber) RCAF

• SGT Gerard Patrick Kelleher (Wireless Operator) RAF

• SGT Douglas James Hicks (Rear Air Gunner) RCAF

• SGT William Towle (Acting Mid Upper Air Gunner, usual role is Rear Air Gunner) RAF

AIRCRAFT:

FLIGHT NOTES:

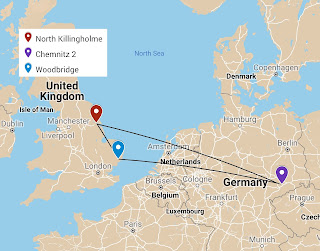

The crew took off at 20.10 and returned the following morning at 05.41, for a total flying time of 9 hrs 31 mins (night) for their first of two raids on Chemnitz (the second would come on March 5). Tonight, Ditson’s mid-upper air gunner role would be filled by Sergeant William Towle. The crew experienced issues with the hydraulic system and had to land at an alternative airport at Woodbridge. The plane checked out and they continued back to base.Following is an excerpt from the Ex Air Gunners ‘Short Bursts’ newsletter March 2005 contributed by Douglas Hicks:

North Killingholme, Lancashire, was the home of the Royal Air Force 550 Squadron. This was a heavy bomber unit flying Lancaster Bombers. The Lancaster, a four-engine bomber, used Rolls Royce water-cooled V-12 engines. The aircraft was very rugged and was the mainstay of the R.A.F. bomber force. On this squadron was one very distinguished Lancaster, named “V”, for Victory. Its first crew called it, “The Vulture Strikes”. Although amateurishly done, the name was painted on its nose along with a rendition of a vulture. Although not kept up to date, there were bomb symbols that indicated the number of trips that the aircraft had made over enemy territory. When we were assigned this aircraft, there were in excess of 70 bomb symbols. Its claim to fame was that it had safely completed more than ninety trips over enemy territory. The latest crew assigned to this aircraft, “V”, had completed their required 30 trips and were now on leave. The practice, when a crew was on leave, was to lend the aircraft out to an inexperienced crew, who had to ‘sort of win their wings’ before being assigned their own aircraft to use on future trips. On this date February 14, 1945, we were the inexperienced crew using “V.”

Target tonight is Chemnitz. It was only our second trip, but we were using “V,” The Vulture Strikes. We felt safe in a sense, using this aircraft, as it seemed almost invincible. We had no difficulty over the target, but upon return to England we found that there was some problem with the aircraft’s hydraulic system. This we accepted knowingly, as old “V” was getting on in age, and we had encountered other problems on previous flights. The procedure in the RAF was, when trouble was encountered, you would not use your home base, as the possibility of having a bad prang would render the home base useless to other returning aircraft. We proceeded to the alternative airport, Woodbridge, and landed safely, even without the hydraulics working properly. On landing, we could see a Halifax bomber (another four-engine RAF bomber) off to the side of the main runway. It had landed a few minutes prior to us, slid off the runway, and caught fire. All that was recognizable was the tail section; the remainder was now just a pile of ash. The practice at these emergency airports was to use a bulldozer to push any disabled aircraft off the runway, so as to keep it open and serviceable for other returning, damaged aircraft.

Upon debriefing, as was normal after all trips; I encountered a Canadian tail gunner from another Lancaster that had used this airport because of trouble encountered over the target. It seems while on their final bombing run they noticed another bomber, a Halifax, attempting to evade a German night fighter. The Halifax had taken violent evasive action, and in one of its swings it came up under the tail of the Lancaster, and its nose came into contact with the underside of the tail gunner’s turret. The gunner reported that when he had last seen the Halifax, it was out of control and in a downward spiral. The German fighter then attacked the Lancaster and they were jolted back into reality as they fought for their own survival. When talking to this crew, their concern was not of their own safety or that they had arrived safely at the base, but what had happened to the crew of the Halifax? They prayed that this Halifax crew had been able to recover and land safely. The feeling seemed to be prevalent with all the aircrews and I, myself, would experience these same feelings as my career as a gunner continued.

When daylight came, we two gunners went out to look at his aircraft. There certainly was a huge dent under the tail gunner’s turret. I jokingly remarked to him that when he saw the Halifax coming up and hitting his Lancaster, that he must have been quick to pull his feet up.

Our aircraft, “V” for Vulture, was checked out, and no malfunction was found, so we returned to our home base. “V” had now completed some ninety-four trips.

Some six months, and many more adventures later, I found myself in Bournemouth England awaiting repatriation back to Canada. I made an acquaintance of another Canadian gunner who was also awaiting the trip home to Canada. It turned out that he was the tail gunner of the ill-fated Halifax that had collided with the Lancaster while trying to evade the German night fighter. He told me that the Halifax had not been badly damaged, but the Plexiglas nose section had been sheared off, and the resulting rush of air blew the crew back to the rear of the aircraft. This air stream was so violent and very cold, as it was not unusual to have temperatures of 20 below at that altitude. As they were near the Russian lines, the pilot decided to fly over to the Russian held territory, and then the crew would bail out of the aircraft. When they reached Russian Territory, the crew jumped, but the pilot, because of the intense wind and cold, was virtually frozen in his seat. He could not get himself out of the pilot’s seat and so was forced to land the aircraft. All of the crew survived and were later repatriated to England via the well-known Murmansk Route. Russian hospitality was not the best, and seven months passed before they were returned to England. All of the Halifax crew was extremely concerned about what happened to the Lancaster that they had collided with, and it was the topic of many conversations they had while in Russia. They were quite elated when I was able to confirm to them that the crew of the Lancaster was safe, with no injuries, and that I had talked to them.

When I recall this encounter I am somewhat amazed that for a time I was the only person who was aware of the fate of these two bomber crews who met by ‘accident.’ I felt pleased that I was able at least inform one crew of what turned out to be a happy ending.

The New Zealander Hicks refers to was actually Australian Maurice Smith. Smith became a POW the same night as Hicks, Kelleher, Nicol and Yemen on March 7th but managed to escape capture.

Comments

Post a Comment